This article first appeared in the Dallas News on May 31, 2013. The article was updated on June 3, 2013.

A relentless vortex of failure steadily yanked at everyone close to Veronica Jacquez, sucking their life dreams away.

As she grew up across the street from the Turner Courts public housing project in South Dallas, Veronica’s father drank heavily and split from her mother. Gang members sprayed her house with bullets.

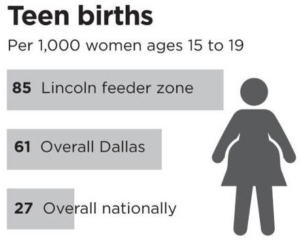

“There was a lot of shooting. The ambulance would be here on a daily basis. Like, no lie,” she said with a shrug, pointing out the bullet holes on the side of her house. “I guess I just kind of adapted to the environment.” Her two sisters became teen moms. Her two brothers got into drugs and big legal trouble. Most of her friends wound up as teen parents. Their career horizons don’t go much beyond cashier, dishwasher or store clerk.

For generation after generation, this pattern has grown so common for families around Lincoln High School in South Dallas that few stop to think anymore about what’s wrong with this picture. That’s just the way life is, the way it’s always been.

With a little help, though, Veronica fought off the vortex and refused to yield her dreams. Now a 19-year-old junior at the University of Texas at Austin, she left on May 24 for an academic trip to Beijing. When she returns in June, she’ll finish her government degree and head to law school.

How Veronica and a handful of her fellow students managed this positive outcome should be the focus of intense discussions as officials at Dallas ISD and City Hall try to reverse the generations-old cycle of poverty around Lincoln. Superintendent Mike Miles and Mayor Mike Rawlings say they want to transform the Lincoln area in the same radical way that led to Harlem’s rebound in New York over the past decade.

Powerful forces are working against them. Miles faces sustained opposition to his educational reforms. Budget constraints, distractions and City Council lethargy are Rawlings’ worst enemies. Add to that the urban decay and academic failure around Lincoln that have been wrecking countless lives decade after decade, and you’re left with a strong temptation to give up and let the vortex win.

But there are compelling reasons, Veronica among them, to believe a major turnaround can happen. Lots of people north of the Trinity River and Interstate 30 believe that poverty and urban decay are the fault of southern Dallas residents. So why waste our tax dollars trying to fix the problem? Others argue that this city has allowed racial and social disparities to fester ever since Reconstruction, so it’s everyone’s job to find a solution.

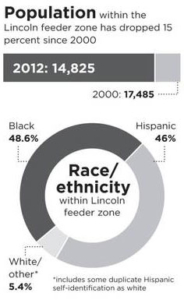

Many generations have grown to adulthood as this argument surged back and forth, yet shockingly little progress has been made to correct what this newspaper calls Dallas’ north-south gap. Whites have steadily moved farther north to get away from it. Wealthier blacks and Hispanics also have fled.

What’s left are increasingly high concentrations of poor minorities who see no way out. And the best promise our elected officials have made to them is: Don’t lose hope. It’s going to take decades, but we will fix the problem. That’s an insufficient answer. Let’s instead aim for something that starts now, shows some fast results and really will fix the long-term problem.

Solutions have been, at best, piecemeal so far. Some chipped away at poverty, others at education or housing. One thing nobody’s tried is to attack it from all sides, all at once. This all-out approach is exactly what we must do if we want to turn around thousands more lives like Veronica’s.

The singular, overarching goal must be to ensure those kids thrive academically so that they become the ones to halt the cycle and lift themselves out of poverty. But it can’t just happen in the classroom. The transformation has to happen in the home and on the streets, too.

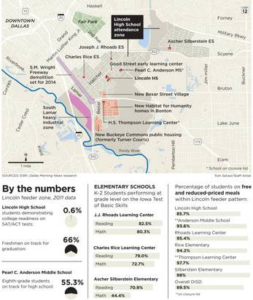

Sounds pretty pie in the sky, I know. But it’s already happening on a small scale in the neighborhoods comprising the Lincoln feeder zone. Similar efforts are getting started in the nearby Madison High School feeder zone, near Fair Park, and around L.G. Pinkston High School in West Dallas.

All three feeder zones have nearly 100 percent minority, economically disadvantaged student populations. All three have been devastated by drugs, high crime, awful housing and longtime exposure to heavy industry next to residential neighborhoods.

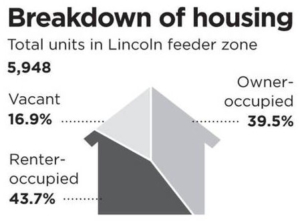

But major new housing developments are cropping up around Lincoln, including an entire subdivision being rebuilt by Habitat for Humanity and designed to boost responsible home ownership. Veronica’s house, and several others on her block, are Habitat homes. Altogether, Habitat has built 109 homes, repaired 19 and invested $12.2 million in Veronica’s neighborhood and nearby Bonton.

Turner Courts, for decades a feeder zone for drug crime and poverty, has been razed. In its place is Buckeye Trail Commons, a 27-acre new public housing project that includes single-family homes and senior housing. Other dilapidated housing in the nearby Ideal neighborhood has been replaced with subsidized townhomes and new storefronts. Opportunities for small-business growth are accompanying the demolition of S.M. Wright Freeway and its conversion to a more pedestrian-friendly boulevard.

But then there’s the vortex. Scores of other blocks are descending deeper into decay, with houses crumbling, streets lined with uncollected bulk trash, heavy drug trafficking and lots of vacant storefronts. Unless something happens beyond piecemeal fixes, all the shiny, new stuff will eventually be sucked under.

So how did Veronica escape? In middle school, she heard about a program called Turner 12, founded by Lincoln coach John Carter. Every five years, he starts with a new group of eighth-graders and sticks with them through graduation. At the beginning, he proposes a contract. The students and their parents must agree to a rigorous program of at-home reading and studying, after-school study sessions, evening meetings with mentors and required community volunteer work. Parents are required to be involved, with their duties spelled out in the contract. Students must maintain no less than an 85 grade average.

In exchange for abiding by the contract, Carter makes one promise: to get them all the way through high school and into college. Veronica was one of the 12 students chosen in 2005.

The same program helped Ivory Alexis, 19, work through lots of anger issues associated with his father’s incarceration when Ivory was 11. Ivory is now a junior at an Arkansas university. Then there’s Jeniece Madison, 20, whose father walked out when she was around 7. He rarely paid child support, so growing up was a constant financial struggle. She’s now a sophomore at UT-Arlington, majoring in finance.

Carter says it’s often a struggle to get parents to embrace the spirit of Turner 12. Since they themselves didn’t grow up with involved parents, he said, they don’t always see a reason to do things differently. He sees the transformation model used in Harlem as “a great idea … but you first have to make the parents want to be on track.”

It will take hundreds, perhaps thousands, of equally devoted parents and educators like Carter to turn things around. The Lincoln feeder zone is overdue for a bold, transformative effort. Miles says he seeks a transformation modeled after the Harlem Children’s Zone in New York.

Harlem was the vertical equivalent of the Lincoln area’s horizontal sprawl. Longtime Harlem resident Geoffrey Canada spent decades watching the steady degradation of his upper Manhattan neighborhood. It had long been infamous as an impoverished black ghetto riddled with crime, drugs and violence.

Canada saw successive generations of kids grow up in horrific conditions — decrepit tenement housing, terrible health care, bad nutrition. Parents were neglectful, having been raised themselves by neglectful parents. Teen pregnancy rates were high.

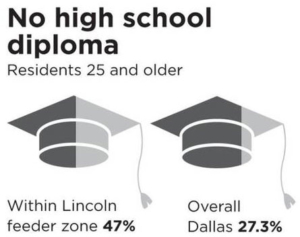

Harlem kids received substandard public-school educations. Adults had minimal expectations of youths if they finished school. When those kids grew to adulthood, they passed the same ethos of minimal expectations to their children.

A decade ago, Canada took on the personal mission of finding out how to reverse this cycle and replace it with a system of high expectations, academic rigor and radical, top-to-bottom social transformation. He sought a fix for every major problem that was helping drag the neighborhood down and perpetuate the cycle of poverty. If a problem couldn’t be fixed, at least its negative effects on children could be neutralized.

Canada designed various intensive programs that remain in place today. One was a successful charter school system that competed to raise the standard of public education. Another was Baby College, which teaches parents how to be parents. Another focuses on formation of neighborhood associations and civic involvement.

It’s time to stop thinking of educational deficiencies as being the sole problem of teachers and principals. Fire them all you want, but you can’t fix schools in places like South Dallas unless the surrounding community also gets a substantial upgrade.

While Carter has been successful starting in middle school with students like Veronica, the best chance to transform students’ lives is in early childhood. If you can get to them well before the third grade and instill good nutrition, a stable and nurturing home environment and high-quality instruction at school, research shows, children have a much higher probability of graduating from high school and going to college. The longer you wait to reach a struggling student, the lower that child’s chances because of the mighty forces on the streets working to drag him down.

The predictable troubled path looks like this: The child tends to lag in literacy and socialization skills and is far more likely to drop out and be unemployed. Many hook up with criminal elements and either head to prison or to a life near the poverty level. The Children’s Defense Fund calls it the “cradle to prison pipeline.”

How early do we need to catch these children? The gap between whites and minorities starts in the womb with prenatal care. There’s a much higher tendency among pregnant poor women not to follow proper nutritional and health guidelines. By the time an infant reaches 9 months, black babies on average are already behind white babies on cognitive development. By 24 months, that gap triples, according to research compiled by the Children’s Defense Fund.

It’s not a racial or ethnic thing. It’s a poverty thing.

The gap is narrower between Hispanic toddlers and whites. But by kindergarten and first grade, both minority groups are less likely than whites to have had regular mealtimes and been exposed to books. Lower-income parents tend to use baby talk instead of enriching children’s brains with thousands of new words they need.

“Really, it’s the vocabulary,” said Susan Gillman, a DISD prekindergarten teacher. “Nobody’s talking to them at home. There are no books, no trips to the zoo.” Instead of telling the child, “Bring me that green pencil by the telephone,” the parent tends to point and say: Give me that.

Gillman teaches at the Good Street Learning Center, a church-supported day care near Lincoln certified to provide classroom instruction for 3- and 4-year-olds. DISD maintains a classroom there.

The nonprofit group Educational First Steps has partnered with Good Street and scores of other facilities to change the standard day care format, where young children are dropped off for baby-sitting and often receive passive adult attention, minimal classroom instruction and lots of time in front of a television. Instead, EFS wants facilities like Good Street to become the new model.

At Good Street, there’s no such thing as baby-sitting. Classroom instruction is packed with vocabulary, art, number and letter-recognition drills and games. Kids work at computer consoles. Everything is designed to be fun but also challenging and educational. These kids stay on track and perform at least at grade level through third grade, Gillman said.

Andraya Anderson-James, a second-grade teacher at nearby J.J. Rhoades elementary, has a doctorate in early childhood education. Her 3-year-old son, Myles, attends Good Street. She said it’s obvious among her own students which ones have been through a quality early-learning center and which ones haven’t.

She also notices differences in their parents, in terms of their involvement and attention to good grades and developmental skills. Parents who haven’t been exposed to quality day care tend to be dismissive and disengaged. “It’s like they don’t care,” Anderson-James said.

Without vigorous early intervention, children start behind and stay behind. They tend to have more absences, increased disciplinary problems and higher likelihood of suspension or expulsion. From there, it goes from bad to worse.

The big challenge is convincing parents that academic underperformance doesn’t start in the schools but in the home. Canada made his case directly to the parents of Harlem but did so in ways that won their enthusiastic support. Who’s doing that in Dallas?

Lincoln graduate Ken Smith, 60, is leader of Revitalize South Dallas, a nonprofit advocating for economic redevelopment and job creation. He says the community must lead the fight for change.

“Schools are like windows into our homes, and children bring that transparency to school daily,” he recently wrote in a Dallas Morning News column. Too often, he says, the community remains disengaged and doesn’t work to instill “moral character, respect and citizenship in our children.” It’s as if parents are leaving schools and teachers to do it.

Dallas ISD trustee Bernadette Nutall and City Council member Carolyn Davis, who both represent the Lincoln and Madison feeder zones, traveled to Harlem last year to see whether Canada’s model might work in Dallas. Both returned mildly optimistic. But it’s clear their enthusiasm is dampened by the fact that Miles also seems to be backing such a program. Nutall is particularly leery, having had bitter public clashes with Miles recently over his educational reforms.

Nutall has pressed Miles repeatedly to explain his intentions for the Lincoln feeder zone and received no response. Last year, after Rawlings called for establishment of a culinary institute at Lincoln as part of his GrowSouth initiative, Nutall grew incensed when Miles failed to provide funding for food-preparation training facilities.

She also was badly burned politically last year when she supported closure of 11 DISD schools, including three in her district. Two Lincoln feeder schools, Pearl C. Anderson Middle School and H.S. Thompson Learning Center, are among them. The NAACP organized protests against her.

Both Davis and Nutall have publicly criticized Miles’ efforts to fire principals and teachers in low-performing schools. Nutall wants more details before she publicly supports what Miles proposes for the Lincoln area.

In an interview, Miles said he expects some second-guessing about his plan but believes the community will rally behind it once the benefits become clearer. He says the culinary arts institute will go forward. He has big plans for intensive tutoring at the middle school and high school levels, with one or two students per tutor. There will be more psychologists and social workers. Lincoln students will envision futures that include college and professional careers.

Miles and critics like Nutall at least share common ground in acknowledging that significant reforms of troubled southern Dallas schools cannot happen without transforming the surrounding community.

These problems cannot be tackled in the kind of piecemeal fashion that has failed southern Dallas repeatedly in the past. When big initiatives get launched and go nowhere, it only helps deepen public doubts on both sides of the north-south gap that significant change will ever happen.

If Dallas wants these fixes to work, we cannot do it halfway or on the cheap. It’s got to happen now, using existing resources, with no more delaying tactics and excuses about tight economic times.

Veronica Jacquez is living proof that the challenges of poverty can be overcome, given the right amount of nurturing and attention. Imagine South Dallas filled with such success stories. And what that would mean for our entire city.

Tod Robberson is a Dallas Morning News editorial writer. His email address is trobberson@dallasnews.com.